It was an elm, wizened by years, roots below grown deep and weighty in Hastings College soil, branches wide above offering shady embrace, and it greeted all—students, alumni, families—from its post at the corner of 12th and Elm.

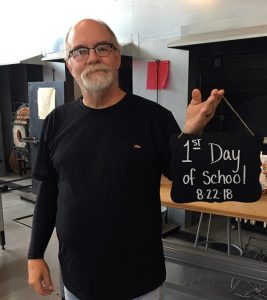

In 1990, Hastings College greeted 10 new faculty, including Tom Kreager, who became assistant professor of glass. A native of Sylvania, Ohio, Kreager had earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts from The Ohio State University and a Master of Fine Arts from the University of Illinois; he was expecting to stay at Hastings “a couple of years at the most.” The glass studio was meager in size, while the sculpture studio truly miniscule.

For an artist and instructor who had served as an artist-in-residence with Dale Chihuly at the legendary Pilchuck School near Seattle, Washington, as well as a graduate instructor the Tokyo Glass Art Institute, Hastings College was to be no more than a quick stop along the highway of Kreager’s career in the international world of glass and art education.

But that brief interlude at a small Nebraska college didn’t mean Kreager would simply bide his time. He began to host visiting artists, many whom he had met during his tenure at Pilchuck, including Scott Benefield, Deborah Dohne, Jim Cook, Leslie O’Brien and Mitchell Gaudet. For his students, sharing the glass studio with towering figures in the glass community became commonplace.

Kreager continued to cultivate such relationships for the benefit of students by teaching at Haystack Mountain School of Crafts and Penland School of Crafts; for six years, he served on the Board of Directors of the International Glass Art Society. Always anxious for improvement to the program, he founded an annual glass auction, proceeds from which benefitted student artists and equipment maintenance.

His “couple of years” stretched to more than two decades. Kreager is retiring from the College this spring.

The elm had borne witness to myriad metamorphoses of the college it guarded. A golf course, of which one green it overlooked, came and went; a football stadium, business and athletics complex, expanded student union, theatre, science center, apartments and alumni center all sprouted and thrived. Beneath the tree, an open meadow now lay fallow, as if to ponder some future yet to be realized.

And then a day came when the visionaries arrived, gesturing and smiling.

In 2010, Kreager met a young man interested in studying sculpture and glass. He loved working in the Hastings College studio under Kreager’s tutelage, as a senior toiling to craft a deer with three-foot antlers and mottled skin. And then he was gone. Jackson Dinsdale found a spiritual home in art, a vessel into which he could pour his energy and enthusiasm for the visual; determined to maintain the memory of his student, Kreager began conversations with his parents, Kim and Tom Dinsdale, about a fitting legacy for their late son. What initially seemed humble, a quiet monument for an altruistic young man, gradually transformed into a grand design: A memorial art center dedicated to nurturing generations of students interested in learning about the arts.

Those who knew the elm well looked on in reverence as it departed, an inevitable, yet honorable exodus in preparation for what was to come, a continuance of its essence through postmodernist architecture, a nursery for artistic insight. Where birds once built nests high in its branches, now were born kaleidoscopic eggs beneath steel and scrim. Where fire once would threaten destruction, now it offered expectancy of marvel, community and joy. Upon one wall a harbinger in neon reading “Hot Good, Cold Bad” foretold a phoenix like reincarnation of the elm, in simultaneous transmigration with the role of art at Hastings College.

Determined to establish the legacy of Jackson Dinsdale as a springboard of renewed vitality for Hastings College, in his 25th year of service Kreager oversaw the construction of a marquis center for art in the Midwest, the Jackson Dinsdale Art Center (JDAC). Its sculpture studios now expansive and its glass studio the finest of any institution in North America, he refused to look inward, opening the arms of the JDAC to campus, colleagues and community in order to begin restoring the sense of connection and goodwill he felt vital to the success of Hastings College.

“Hot Dogs, Hot Glass” days drew dozens of faculty, staff, students and community members for the theatrical demonstrations of glass blowing once a month. Organizations throughout Hastings were welcome to host events free of charge, often accompanied by complementary glass blowing demonstrations. “Glass is a community,” Kreager was fond of saying, a concept he refused to limit to artists alone, ensuring the legacy of a professor who wanted nothing more than to celebrate to the fullest the arts, all students, and Hastings College itself.

Outside, the spirit of the elm peered lovingly through the northwest windows, admiring the creative spirit its absence had fostered. Generations of glass blowers—and legions of artists and admirers—had convened to pay tribute to the teacher whose vision, love, and selflessness nurtured new forests of artists far afield. Immortality met both elm and educator.

And it was good.