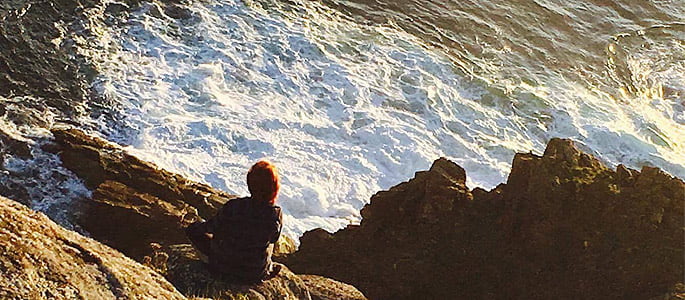

Perched on a rocky landscape overlooking a seemingly endless horizon of water, Jenna Jaeger, sophomore biology and Spanish double major, sat quietly meditating after a five-day trek through Northern Spain. The quiet moment gave her a chance to reflect on the 72-mile hike she’d just completed during January Term (J-Term) 2017.

While many students use J-Term as an opportunity to travel abroad, Jaeger and six other Hastings College students set out on a J-Term trip that led them to the end of the earth — and into a new culture.

Accompanied by Dr. Pedro Vizoso, associate professor of Spanish, and Dr. David McCarthy, professor of religion, the group explored the French route of the Camino de Santiago.

“The Camino de Santiago is a very old tradition in Europe, and pilgrims from everywhere used its routes to journey to Santiago de Compostela, the location of Saint James’ tomb,” Vizoso said. “The French route is the most common because, in some ways, all the pilgrims going to Santiago de Compostela from the European Countries east of Germany were funneled there through Paris.”

The Camino de Santiago played a large role in the development of Spain’s religious identity in the eighth century. For nearly 800 years, Spain was under the control of the Islamic Moors. Spain embraced Catholicism as a way to create a distinct identity and recover from Moorish rule, with Christianity spreading throughout the country via the Camino.

The goal of the J-Term course was to study the culture, religions and history of Europe by experiencing the Camino de Santiago first-hand during a three-week trip through the cities on the French Route.

Exploring France as Spanish speakers

The adventure began in Paris, France, where the class traveled by car to the French stops on the Camino. The students presented mini-lectures in Spanish about the importance of each French city along the way, and they explored the major cathedrals related to the Camino’s rich history.

France helped the students — who were each studying Spanish as either a major or minor — to step out of their comfort zone and into a new culture and language. The students could rely on Vizoso and McCarthy for most translations; however, when they set out by themselves during their free time, they were challenged to adapt.

“We had to learn about French culture in order to not be obnoxious tourists. I learned a little bit of the French language, too” Jaeger said. “I value my Spanish education much more after my experience of not being able to sufficiently communicate in France.”

McCarthy, who holds a Master of Arts in French and a Doctorate in religion, shared valuable insights and history lessons to help students navigate a culture distinct from their Spanish studies.

“Although I speak French, I didn’t know the French steps of the Camino,” Vizoso said. “Dr. McCarthy explained the significance of every step we visited in France, so I relied totally on him to do the French portion of the trip. For me, Dr. McCarthy was an amazing help.”

As the class wrapped up their lessons in France, they prepared to cross the border into Spain. Although their route on the Camino was continuous, the culture and language would change as they journeyed south.

“Just imagine if the United States was divided into 27 countries, and every country had its own language. Going from France to Spain would be like crossing the border to Kansas and suddenly having to speak another language,” Vizoso said, noting that it was good for the students to experience Europe’s cultural diversity by exploring the continent’s history.

“It was such a stark difference. France seemed a little more proper, posh and affluent, whereas Spain was more laid back, happy and accepting,” said Joseph Quinn, a junior Spanish and education double major. “There was even a difference with how churches were built in France and Spain, which was really interesting to see.”

A pilgrim’s voyage

Once in Spain, the class embraced the true history of the Camino by finishing the final 72 miles (116 kilometers) on foot. For five days, they walked from city to city on their way to Santiago de Compostela.

Once in Spain, the class embraced the true history of the Camino by finishing the final 72 miles (116 kilometers) on foot. For five days, they walked from city to city on their way to Santiago de Compostela.

“We tried to live like pilgrims as much as we could by staying in pilgrimage hostels and living with other pilgrims,” Jaeger said.

Unlike some of the pilgrimages, the trip didn’t end when they reached the site of Saint James’ tomb in Santiago de Compostela. Instead, the travelers continued on, driving to the zero kilometer or “true end” of the Camino.

“The tradition of the Camino de Santiago often ends with going to the zero kilometer of the route at Finisterre, or the end of the earth. This is where the Atlantic Ocean begins, and the land ends in a cliff with an abrupt drop into the sea,” Vizoso said.

Vizoso said his students seemed to be strongly affected by their stop in Finisterre. For Jaeger, it was a quiet space to reconnect with herself after the strenuous trip on the Camino.

“I was able to sit and meditate while listening to the ocean and absorbing the sun,” Jaeger said. “During this trip, I really connected with myself, and meditating at Finisterre gave me a sense of the strong spirituality in the place, and a sense of peace.”

Immersion in history, culture and language

The students’ return to home just a few days after their visit to Finisterre revealed improved Spanish speaking skills and an expanded understanding of Spanish culture. While abroad, the class was required to speak in Spanish as often as possible. Vizoso said limiting the student’s’ ability to use English enriched their learning experience.

“When students are constantly using Spanish in their interactions, they are in some ways able to connect with the physical reality of the culture,” he said. “Making that physical connection with the target language and culture is so important because it makes the trip more than just a tourist experience.”

Even after two full years of college Spanish courses, Jaeger said her experience on the Camino was distinct from anything she had learned in the classroom. Full immersion in the language helped her to grow her Spanish repertoire.

“Sometimes, colloquial terms would get in the way of our somewhat limited Spanish vocabularies, but it forced us to learn more and expand our Spanish knowledge,” Jaeger said. “There was no longer the easy way out of explaining it in English — we had to find a way to say what we wanted in order to communicate.”

Traveling through France and Spain pushed the students to “pop the university bubble” and immerse themselves in history, religion, culture and language, said Vizoso. For the seven scholars who completed the Camino de Santiago for J-Term, the impact of the unique experience will be long lasting.

“Leaving your own country and culture will take you out of your comfort zone, but it will open your eyes to understanding something that’s different than your normal routine,” Quinn said. “This J-Term class was an opportunity to see the world in a new way, and it was life changing.”